The text below was written by John Kenneth Marshall (aka Kenny).

Hugh Grant Forrester : John Stevenson 1872 – 1943

On his Mother’s side he came from Shropshire farming stock.

Harriet, Grandad’s Mum, was Mary Ann Martin’s second daughter. She was born in Cheswardine, although she clearly didn’t know that because she was described in the censuses as being born in Hanley, where she lived as a child. (In 1881, our start point, the enumerator wrote Handley, Yorkshire, which effectively threw us off the trail for some considerable time!). As stated earlier, she was born deaf and dumb. In 1861, aged 10, she is shown as ‘at home’ rather than the usual ‘scholar’ so it may be that she got very little formal education. By 1871, in Liverpool, she was living away from her family in a lodging house. She was a machinist and there is another machinist, an older woman from Shropshire, living there. Maybe they were living over, or near, the shop.

On 7 July 1872 she gave birth to Grandad at her Mum’s house. The Father’s name is not on the birth certificate but she named her boy Hugh Grant Forrester to make it clear who he was. We have two possible candidates. (Since writing we now know that Mark Grant was the father). When Mary Ann married Michael Davies in 1871 one of the witnesses was Mark Grant, a southerner, and it might have been a relative of his. However, we have not been able to find a Hugh in his family. The other was a Scottish seaman who was living in the area. When Hugh was almost five he and Harriet were admitted to the workhouse at about the time that Hugh Grant, the seaman, married another girl. Had he been supporting them in the early years and then left them destitute when he stopped doing so? Possible.

Harriet was in the workhouse from May to September 1877. A fortnight after she arrived her son was taken away from her and sent to the Kirkdale Industrial School. She had to get on with life and she became a dressmaker. In 1880 she married George Brunton Fowler. They had three daughters and a son. The eldest daughter, Harriet, emigrated to the States later, and the boy, George, was killed in World War I, but we used to visit the other two girls, Mary and Martha, when we were little. Visits to ‘Aunty’ Mary were timed to coincide with me needing a haircut. Her husband, John Brown, did the honours in their back kitchen – or was it a neighbour? I forget. They were always referred to as Grandad’s sisters, never as half-sisters. George, the husband, had various jobs but was primarily a seaman. He died some time in the 1890s. Harriet senior followed him in 1900, aged 49. She died of pneumonia and cardiac syncope in the section of the Liverpool Workhouse which was used as an old people’s hospital.

It must have been a traumatic experience for little Grandad to be taken away from his mother and put into the Industrial School when he was still almost two months shy of his fifth birthday. We don’t know why he was taken from his Mum. His admission entry records ‘Father dead. Mother died in workhouse.’ This was patently untrue, and might have been the result of a tired clerk finding the easiest way to complete the formalities, but it’s more likely that the authorities had difficulties in communicating with the deaf-and-dumb Harriet and so assumed that she was sub-normal and therefore unfit to look after a child. So the entry was suitably ‘adjusted’ to justify his removal. I’m afraid that this attitude persisted at least until the 1930s. We had a little deaf-and-dumb girl living a couple of doors away from us and it was taken for granted that she must be simple-minded.

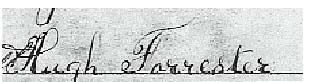

Grandad stayed at the school until 1883, when he was almost 11, and was then ‘discharged to service’. It could not have been a very pleasant life but at least he would have been adequately, if dully, fed and he probably got a better education than he would have done if he had remained outside. We know that his handwriting was very neat (see below for a picture of his signature when signing on a ship some 8 years after he had left the school.)

He no doubt got his share of beatings in front of his schoolmates – a ritual which took place each Friday – and probably had to fight others to protect his place in the pecking order, so he would have been quite a ‘hard’ lad when he finally left. One feature of the school was that a ‘ship’ had been built in the grounds and an old seadog used to teach those boys who wanted to learn as much as could be taught of the sailor’s trade without actually going to sea. That must have stood him in good stead in later life.

When he moved into the bosom of his new family he adopted the name of Fowler and it was as Hugh Fowler that Gran, and all his friends, knew him. He kept Forrester as his official name. He was much older than the other children so easily adapted to the role of big brother. He was particularly fond of his eldest half-sister, Harriet Isabella Ruby, and, eventually, recycled her ‘spare’ names to one of his daughters as Isabel Ruby. He lost touch with her after she had married (Hall) and emigrated to the States and although he tried to trace her at a later date he was never able to do so.

We have not yet found any records of his early years at sea, but family legend says that he went round the Horn when he was only 13. That is quite likely. They were the boom years of the San Francisco grain trade which was largely controlled by Liverpool merchants and mainly carried in British sailing ships. Coal from Liverpool out and grain back to Liverpool. The nitrate/guano trade in sailing ships from Chile was also flourishing.

Grandad was born with a caul.1 He carried it throughout his time at sea as a talisman against drowning. When I went to sea Gran wanted to give it to me but, regrettably, it could not be found. Never mind, I didn’t drown anyway.

The earliest record we have of him is as an ordinary seaman aboard a coastal sailing ship (brigantine) in 1891. He left her in Burry Port (South Wales) on 16 April. The next record we have is of him joining an American four-masted schooner in Pensacola on 4 December 1891, using the name John Forrester.

So some time in the intervening six and a half months something happened which caused him to change his name. The family story is that he accidentally killed a man in South America/South Pacific and jumped ship to avoid any possible retribution, just or otherwise. He then bought the papers of a derelict seaman and resumed his career under his new name. We now know that the name changed over a period of time, and it’s possible that the incident happened in the American South (i.e. the USA) rather than South America. No certainty, though. It could be that the incident did happen in, say, Brazil, or the West Indies, and he then took a ship up to the States from there. We have so far been unable to find any hint of what happened, despite a rigorous search of deaths at sea records and such newspaper archives as we have been able to access. But maybe someday someone will stumble across something and all will be revealed.

He left the schooner in Philadelphia and so severed his connection with sailing ships. Thereafter he only sailed in steamships, where the pay was better. Those big schooners were the final technological attempt to make sailing ships more competitive by reducing their manning. They traded successfully on the American coasts until the 1920s but they were not quite so successful deep sea because they had a disconcerting habit of capsizing.

In April 1892, still using the name John Forrester, he joined a ship for UK as AB. As he was persona non grata with the British consul in Philly (having officially deserted) he had to follow the custom of the port and use the services of a crimp, either voluntarily or involuntarily, to get the job. This meant that the crimp received 90 dollars for his services and Grandad received nothing. Known as ‘working his passage’.

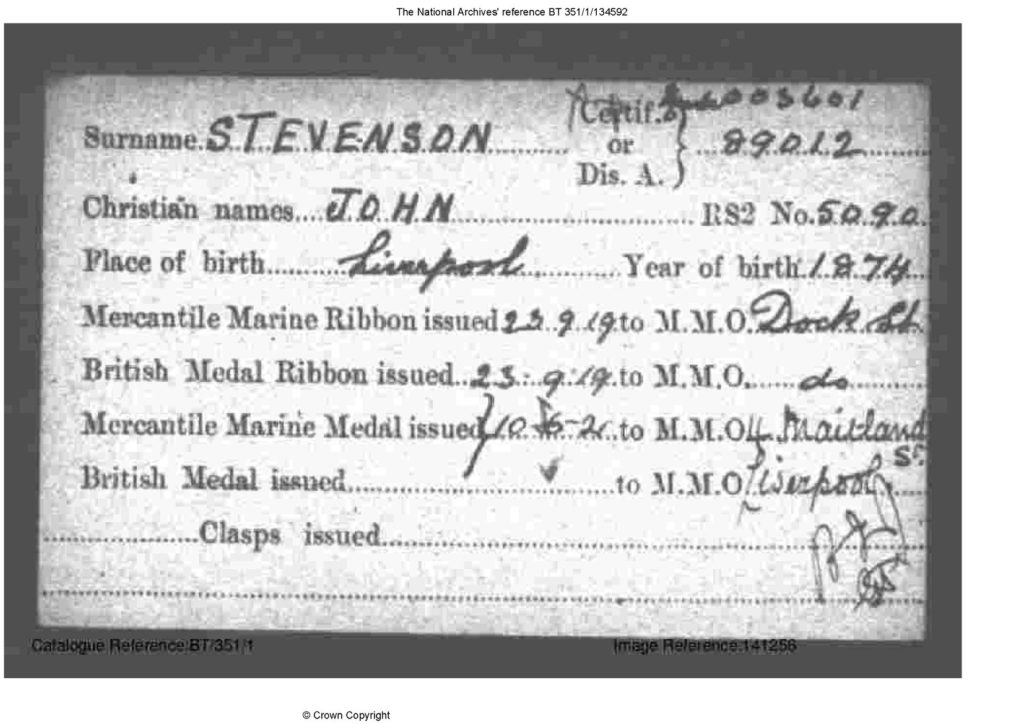

He stayed at home for a while and then on 25 July 1892 he used the name John Stevenson for the first time when he signed on the Lord Charlemont for a voyage to Baltimore. He always used it after that, but for some strange reason he often gave a false place of birth until 1894. The fact that he went back to the States suggests that whatever his problem was it was not with the American authorities.

Any thought that he might settle down to a quiet life were soon dispelled. On Christmas Day 1892 he was aboard the Tropea in Falmouth. She had originally sailed from Liverpool for Galveston, Texas, but had put back to Falmouth after she broke her main shaft. The cook ‘was not a superior one’ and there was a fracas at the Christmas dinner because he had ‘not peeled the spuds’. After pelting him with spuds, one of the seamen threw a knife at him and the police were called. Next day the ship was due to sail but several of the crew refused to do so because the food was so bad. They were prosecuted for refusal to obey an order and pleaded guilty. All but the ringleaders were offered the chance to rejoin the ship if they paid the expenses of their actions but they declined and were sentenced to three weeks hard labour in Bodmin Gaol. Grandad was amongst them; See Extract from The Falmouth News Slip Saturday, December 31st 1892 A CHRISTMAS DINNER SQUABBLE AT FALMOUTH 2

He went back to sea in May, sailing from Blyth. Thereafter, apart from a brief spell in 1897 when he tried his luck in South Wales, he made Blyth his home port until 1903 when he switched more permanently to South Wales. He must have had talent, as well as being a hard man, because in 1895 he was promoted to Bosun and Lamptrimmer at the tender age of 22. He reverted to AB when he changed ships.

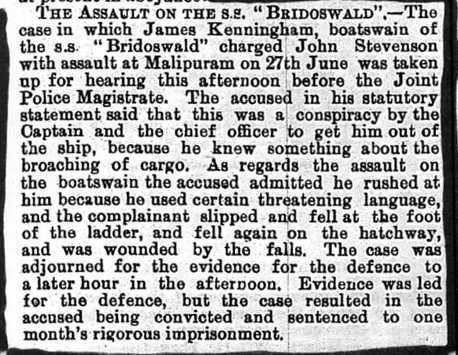

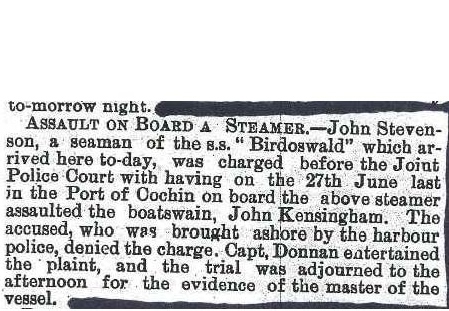

In 1896 he joined the Birdoswald on a voyage which meandered around the Indian coast for months. That it was not a happy ship is demonstrated by the number of people who signed off the ship in sub-continental ports. Even the Mate did so. At one time they were anchored up a creek near Cochin in the wet and sticky monsoon for six and a half weeks, presumably awaiting a charter. Tempers would have been somewhat frayed. Grandad’s certainly was because when the Bosun said something offensive to him he thumped him. The Bosun probably called him a bastard. A common enough cuss word, but it was generally felt that its use to a person born out of wedlock was a grave insult which invited a violent response. When they arrived in Colombo, a month later, he was arrested and charged with assault. He admitted that he had ‘rushed’ at the Bosun who then slipped and fell at the foot of the ladder and fell again on the hatchway. The Port Magistrate, who first adjourned the case whilst he had his Tiffin, found him guilty and sentenced him to one month’s rigorous imprisonment.

At the end of 1898 he spent his longest period ashore – 7 months. Times were hard for seamen in the depression years of the 1890s so it’s possible that he spent some time ‘on the beach’. But in May 1899 he signed on a brand new ship as Bosun and Lamptrimmer, so it’s likely that he had spent at least some of the time standing by her whilst she was building, watching the owner’s interests.

He had a four month spell ashore in 1900, when his Mum was suffering her last illness and went back to sea after she had gone. He joined a ship which had just been sold to Canadian owners in South Shields. He might have thought that he was just doing a delivery voyage but when they got to Canada they kept the crew aboard whilst she traded around the Great Lakes. He is shown as having deserted in Detroit on 11 September, but it’s at least possible that he had just missed the ship by being late getting back from ashore. It was not unusual for Captain’s to ‘hope’ that their crews deserted so that the ship kept their pay and they would not be saddled with repatriation expenses if the new owners decided to have a Canadian crew. We don’t know how he got back to the UK. He might have come back as a passenger (unlikely), a stowaway or on a foreign ship.

He next signed on the Basil for a coasting trip from Blyth to London in February 1901 and it was from the crew agreement of that trip, found by chance in the Liverpool Record Office, that we were able to begin tracing his previous ships.

Immediately after that he was issued with his first Discharge Book, a continuous record of the ships he sailed in. I have it. He sailed variously as Bosun (& Lamptrimmer at times) and AB until 17th May 1905 when there was a life changing event. He was five months into a voyage as Bosun/Lamptrimmer when something happened to the Old Man (Captain). We know not what. So the Mate took command, the Second Mate became Mate and Grandad was promoted to Second Mate. He was two months in the job before they got home, and it obviously gave him a taste for life on the bridge. He had six weeks ashore when he got home, probably spending time at school with a view to getting his ticket. He did a couple more voyages on deck, probably to replenish his funds, then a second six week spell at home, during which he got his Second Mate’s ticket. In June 1906 he signed on as Second Mate for the first time. He never looked back.

He married Gran on 18th November 1907. The story goes that Gran was visited by her priest (she was a Catholic) who told her that if she married Grandad in a Protestant church she would not really be married and all her children would be illegitimate. Thereupon Grandad, who happened to be present, punched him so hard that he broke his jaw! (Possibly a bit of embellishment there.)

He got his Master’s Certificate on 18th December 1909 after little more than a month ashore. That was quick, especially as he had to re-sit the Deviascope exam. Gran told me that he was the acknowledged expert on the deviascope at school to the extent that he used to teach the other pupils how to do it. So it was a great surprise when he dipped (failed). But instead of practising hard for the next week before the re-sit he did nothing – just went out for the occasional pint and so on. He passed the re-sit with flying colours. So her advice to me when I was doing my exams was to behave in much the same way, so that I did not get too uptight with studying. Grandad was 36 when he passed, which is about ten years older than the norm.

He continued to sail as 2nd or 3rd Mate (quite usual at the time) until April 1911 when he signed on as 1st Mate for the first time. He reverted to 2nd Mate later in the year when he joined the Northfield Steamship Company of Liverpool, trading from the coal ports of South Wales to the River Plate. He stayed with that company for more than two years, which was a first for him. He rarely did more than two voyages in a ship and tended to be a one ship one trip man. He rose to Mate after a year and then probably got his first command with them, perhaps relieving one of the regular masters for a trip or two. There is an eight month gap between his last voyage as Mate and his next ship which is otherwise unexplained unless he had sailed as Captain. Captains did not have their voyages recorded in their discharge books. Technically, he was the owner’s representative and the crew signed the agreement with him, not the owner.

He joined the Liverpool & Hamburg Steamship Co (D.Currie) of Liverpool on New Year’s day 1915. The company was known to all as Donald Currie’s. He did one trip as 2nd Mate, one as Mate and then became Master. We have a photograph of him in the company uniform. How long he stayed with them we don’t know but family legend has it that eventually he fell out with the owners and stalked off in high dudgeon. However he continued to sail as Master (Captain) until 1922.

I have his ‘Submarine Menace’ Certificate (marked ‘Not to be taken to Sea’), awarded on 14th June 1918 at Chatham, when he was Captain of the Wad Lukkus, owners Matthews and Luff.

In 1918 he volunteered to take the first ship through the minefields up to Antwerp. For this he was awarded a medal according to family lore, but we have not been able to find a record of it.

He reverted to sailing as Mate for a year between 1922 and 23. Times were hard for sailor men as the post-war shipping depression began to bite. However, he was promoted to Master of the ship (Wyke Regis) before he left her and thereafter stayed as Master for what was left of his career. Whilst he was Mate his eldest son, Hugh, did his first paid trip to sea with him.

Of note is the fact that of 42 voyages recorded in his Discharge Book only one of them commenced on Merseyside, where he lived and took his exams and which might have been expected to be his first choice for employment. Maybe this was because he did not want to use the Liverpool shipping office in case someone who knew him as Hugh Fowler greeted him as such when he was trying to sign on as John Stevenson.

The ‘Description of Voyage’ for all his later voyages is ‘R.A.’, meaning Running Agreement. This was an agreement for multiple voyages within a six month period. (A Foreign agreement was for one voyage of up to two years duration.) This indicates that he had given up roaming around the world and had settled for short sea voyages so that he got back to this country more often. When he did not have time to get home Gran used to go to whichever port he was in to see him. My Mum remembered going with her when she was a little girl. Later they used to go to sea with him for a couple of weeks at a time.

By the late twenties he was Captain of the coaster Ribblemere (built in 1925 and owned by John S. Sellers) on which my Father was Mate. It was Dad who first told me that the crews called Grandad ‘Frostyface’. Others confirmed that. Uncles Hugh, Jack and George also sailed with him at some time. I have the full year’s record for 1928, which shows Dad, Jack, Gran and Mum aboard at times.

He grew wealthy enough to buy the 12 roomed, 3 storey house at 40 Newstead Road in 1929. Not many people owned their own houses at that time. (Nor for long after that. Neither my parents nor Glenys’s parents ever owned their own house.) The house no longer exists.

Ribblemere was Sellers’ biggest and newest ship. Their pride and joy. But as the depression began to bite ever deeper Sellers decided to retrench (or ‘downsize’ in today’s parlance) and Ribblemere was first to go. She was sold in 1930. It’s possible that Grandad had the chance to go with the ship to its new Cardiff owners, as was common practise, but decided to stay with the Liverpool firm. If so, he must have regretted that decision later on.

He transferred to the Abington, the second largest ship in the Sellers’ fleet. Then, in 1931, the roof fell in thanks to a spot of inter-governmental tit-for-tat. Examination of the Ribblemere voyages in 1928 show that in the spring and summer 40 percent of her loads were in the Brittany trade. (Over 50 percent at the height of the spud trade.) Coal there and spuds back. So it was probably Seller’s biggest earner. But in 1931 the French government banned the import of Welsh coal in order to help the miners of Northern France who were suffering – as were ours. The UK government retaliated by banning the import of French potatoes on the pretext of concern about the possibility of Colorado beetle infestation (which the French vehemently denied.) So between them they effectively ruined Seller’s business and, incidentally, also ruined the economy of Brittany. Bretons were considered to be a pesky nuisance by the central government, so they would not have worried about that. Sellers had to cut back again, so the Abington was sold to Manx owners. This time there was no chance of Grandad going with the ship because Manx owners were noted for using only their own three legged captains. So he was on the beach with a vengeance in those hard times. I believe that was the end of his career at sea.

Sellers continued to suffer in what was the worst trade depression since Adam was a lad and in 1936 they sold all their remaining ships including Ribblebank where my Dad was Skipper. He moved with the ship. Perhaps his funny handshake helped him.

So in the thirties, when I knew him, Grandad was unemployed. He sent his medals back to the authorities and said that he would sooner have a job, but to no avail. Gran used to say that he had been a very good husband until then but that he got in with some bad company at the Lodge Lane Baths, where the unemployed used to gather to while away the time, and he started gambling.

He used to keep his hand in at his sailorman trade by washing down the back yard. He would be fully dressed in his thigh boots and took charge of the hose whilst we kids did the scrubbing in the approved nautical manner that he showed us. To say he was a bit intolerant of any mistake would be putting it mildly. My Mum often had words with him about his attitude to us kids. However, he was not all ‘hard’. Occasionally when we found him alone he would slip us a threepenny joey (coin) with the admonition not to tell Mam or Gran.

During the war he took a job as a

firewatcher, which meant that he set off each evening and spent the night on

the roof of one of the city offices spotting fires during the air raids. In 1943 he contracted pneumonia whilst doing

so. On Saturday 21st August I was on my

way to see Liverpool playing Everton at Anfield. I used to walk up to Gran’s from Penny Lane

and then get the 27 tram to the ground.

But this day she asked me to run to the Doctor’s in Upper Parliament

Street to tell him that my Grandad was very ill. (Telephones were still a rich man’s

prerogative in those days.) I did so,

and the doctor came right away. He went

into hospital on Monday 23rd but at 2.15 a.m. on Saturday 28th August 1943

dear, gruff old Frostyface breathed his last.

- A child “born with the caul” has a portion of a birth membrane remaining on the head. In medieval times the appearance of a caul on a newborn baby was seen as a sign of good luck. It was considered an omen that the child was destined for greatness. Gathering the caul onto paper was considered an important tradition of childbirth: the midwife would rub a sheet of paper across the baby’s head and face, pressing the material of the caul onto the paper. The caul would then be presented to the mother, to be kept as an heirloom. Folklore developed suggesting that possession of a baby’s caul would give its bearer good luck and protect that person from death by drowning. Cauls were therefore highly prized by sailors. [↩]

- At Falmouth on Monday, before Mr. T. Webber (Mayor), Captain Reed RN, Mr. J. Hunt, and Dr E. Head Moor, borough magistrates, Lawrence Miles, seaman on board the Liverpool steamer Tropea, Captain J. R. Barber, was charged with wounding John Hoare, a negro cook, on Christmas day. Prosecutor said he was getting out the plum pudding, when the prisoner and another man asked him why he did not peel the potatoes. Before he could reply they pelted him with potatoes. Prisoner picked up a large knife off the table, and flung it at him. It struck the door first, and then the prosecutor on the left arm, causing a serious wound… Dr A. B. Harris, who put three stitches in the wound, said it might become dangerous.

PC Pratt, of the harbour police apprehended the prisoner, who declared that the cook threw the knife at him first. Prisoner was committed for trial. Joseph Barlow AB, for throwing potatoes at the cook on Christmas day and striking him in the mouth with his fist, was fined 2s 6d and 6s 6d costs, or seven days.

A dozen able seamen and firemen of the Tropea were brought up in custody for disobeying the commands of captain Barber that morning. Their names were Daniel O’Leary, George Lanfield, John Stephenson, Daniel Collins, Thomas Spiller, John Watson, John Doyle, James Bailey, James Henderson, Thomas Gaskin, William Mc Coy and John E. Baker.

Mr. W. Jenkins, who prosecuted characterised the case as an outrageous one. The men all signed articles at Liverpool on November 10th, the Tropea being bound for Galveston in ballast. Whilst on the voyage the main shaft broke and the steamer put back to Falmouth arriving on December 3rd. The repairs were executed and the ship was ready to go to sea on Thursday but the weather was unfavourable. That morning, at half past seven, the captain ordered the men to unmoor the ship and they refused. The captain understood that on Christmas day the men complained that the cook had not “peeled the spuds”. Each prisoner was asked why he refused duty, and in almost every case the answer was that they did not wish to go in the ship on account of the “grub” being badly cooked. The Steward said food in plenty was provided, but the cook was not a superior one. There might be some fault with the bread, but he had seen worse. Lanfield and Doyle were committed to Bodmin gaol for four weeks hard labour, and the others to three weeks each.

Note: Joseph Barlow opted for the 7 days rather than for the 2s 6d fine and 6s 6d costs [↩]